J. Michael Friedman

1.

1.

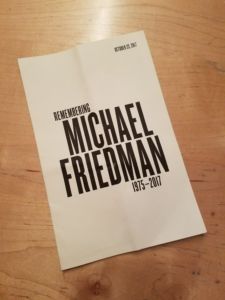

Michael sang at my wedding, but he wasn’t actually there. He was at the airport in Long Beach, having missed his flight. Or, it had been canceled. I can’t remember now. So, he called in. Curtis and Jason and Michael were supposed to sing “I Will Never Leave You” from Side Show, a show-stopping ballad from a show that as far as we knew then only I liked.[1. Eventually, a cult of fans grew around it, and it was revamped and revived, but failed again.] Blonde Siamese twins sing it to each other. It’s ridiculous, since of course you can’t leave your Siamese twin. As Curtis has said repeatedly, “It should be I would never leave you!” It’s also a beautiful song. Jason and Curtis and Michael did sing it together, but Michael’s voice was coming from Curtis’s cell phone. Honestly, I couldn’t hear Michael from my chair however many feet away. Anyway: The song had meaning beyond the joke. My husband Rob and I were leaving New York in a few weeks, and three of my best friends were telling me they’d never leave. I stayed with Curtis for three nights last weekend, and at Jason and Liz’s for another two. They never left me, but Michael did. Last month, he died of AIDS, and on Monday night, well over a thousand people attended his memorial at the Public Theater. Michael sang that he wouldn’t, but he did leave me. He left everyone.

2.

I was having a great day that Saturday. I was still on an emotional high from Burning Man, which I’d returned from four days before. I had a great lunch with an old friend I hadn’t seen in many years. I was having a fun chat with a neighbor when I got text messages from Liz. “Hey there – can I give you a call? Let me know if you’re around or just give me a call.” I saw the texts and then my phone died. Obviously something was wrong, but it could be anything. While the phone was charging, I opened Facebook on my desktop computer and saw that Adam Feldman, one of Time Out New York’s theater critics and a friend of all of ours from college, had posted, “RIP Michael Friedman …”

I immediately started shaking and losing focus and felt deep sobs coming through. I got my phone working and I called Liz. The conversation was at first very confusing because Liz had assumed I knew Michael was sick and that he was sick because he had AIDS. But I was piecing it together and had to ask her if that was what happened. I was crying and I was mystified and I was furious and then I was so agonizingly sad. I called my mother and then I called Rob, now my ex-husband, and then I talked to Cat and Jason. I cried and I cried, and I was alone in LA. The next morning I saw my next door neighbor on the staircase and I burst into tears in his arms.

I posted on Facebook, “Michael Friedman was one of the best friends I’ve ever had, an incomparable talent and wit, probably the smartest man I’ve ever known, and an awesome, hilarious roommate. I now know how it feels to be gutted. I don’t know what to do. I don’t understand.”

3.

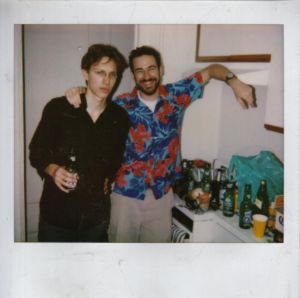

The first time I remember ever seeing Michael Friedman was through the window of the main door to Adams House. He was standing on the sidewalk with female friend, and he was laughing, long hair bouncing, his smile huge. There was then, and forever, even as he grew more serious and a little more likely to be sad or angry, a Muppet quality to his demeanor.[2. I’ve lost count of how many people have used “Muppet” in their descriptions of him, in written remembrances and at the memorial on Monday.] He was 19, probably, and I was 20. I was one of few out men in my class, and I recognized a compatriot. He was so much more expressive, with his vocal inflections and his gangly and gesticulating arms, than straight men, who comport themselves, usually, with much more restraint. But, then, as I stood in the Adams House entry, someone told me the two of them were dating. “Well, okay,” I said with a raised eyebrow. They weren’t; she just had a crush on him. And Michael, as far as I knew, was dating no one. I just assumed he would come out at some point.

Three years later, after Michael had graduated and we were both living in New York and both working near West 57th and 8th Avenue, he called me at my desk at Newsweek and asked if I wanted to go for a walk. We had become good friends over the years, mostly because of the various theater projects he did with close friends Liz and Jason, who would become, along with Catherine, my roommates those first years after college. He music directed their production of Company, and he directed Jason and Cat in Lips Together, Teeth Apart, for which I ran the light board – terribly – for two performances. I didn’t know he wrote music then, but I knew he played, sang, and knew things about music and theater and art and literature and history and politics, more and better than anyone else, though I didn’t realize then just how much better. He was funny as hell, too, and in my favorite way: he would make connections between the rarified intellectual world and populist pop culture (e.g. Kant + Britney Spears = Hilarity.) And we were friends, but we weren’t as close as I was to, say, Liz and Jason and Cat.

Then there was that walk. I thought it was an odd suggestion, since we’d probably see each other that weekend at some party or bar get together. But Liz had told me he needed to tell me something. I knew what that would be. But the way he said it, “It seems I forgot to come out,” made it seem rather matter-of-fact. Now, no one forgets to come out like they forget to pack a lunch or pay a parking ticket. And you don’t take one of your closest gay friends on a walk to tell him that it was an oversight, an oops. I didn’t push him on why he waited, because it seemed that so many people waited until after college, which was frustrating as one of the few, often lonely, gay kids on campus, but it’s hard to begrudge him or anyone else being 21 and not ready or scared or private or just plain neurotic. I suspect with Michael it was all of those things, or most of them. Michael’s interiority was always mostly a mystery to me, and it seems, based on conversations I’ve had in the weeks since he died, it was a mystery to so many people. I may have been privy to things others weren’t, I was clearly not allowed in places others were, and so much seemed only to be experienced by him, alone and uncharacteristically quietly.

4.

While last week’s Sunday Times article and Jesse Oxfeld’s lovely remembrance in Tablet mentioned that he was gay, neither obituaries in The New York Times and The Washington Post, nor the wonderful piece in The New Yorker, reference it, though the “Broadway composer, 41, dies of complications from HIV/AIDS” is enough of a signifier. They focus on his brilliant work, his versatility and wit, generosity and productivity, how he had a million friends, was loved by the theater community like few are, how he was so young and had so much more art in him. I’ve worked as a theater critic and I know Michael’s work pretty well, but I don’t think I can add much to what Alex Timbers or Steve Cosson or Ben Brantley have said and written. I am so sad that there won’t be any new songs and I love his music as much as I do any contemporary songwriter, but if he’d never written a song, he’d have still have been my friend, one of the best friends I’ve ever had, one of my favorite people, someone who I still cannot imagine isn’t going to swoop into town, meet me for a drink, and have with me the most thrilling conversation I’d had since the last time we’d had a drink. If he’d never written the songs in Gone Missing or Bloody, Bloody Andrew Jackson or Fortress of Solitude, I’d still be devastated, gutted, waking up every morning since that Saturday, realizing he’s still gone and feeling like I’ve been hit by a bus, again, again. But if we weren’t both gay, we wouldn’t have had the same friendship, obviously, and maybe less obviously, I wouldn’t be as confused, enraged, and discombobulated that Michael, somehow, in 2017, absurdly, died of AIDS.

4.

One of my favorite memories of living with Michael was the morning we made each other late for work because MTV was premiering the video of the Backstreet Boys’ “Backstreet’s Back.” We laughed at ourselves, at the video, and presented to each other our cultural and aesthetic analyses.

One of my favorite memories of living with Michael was the morning we made each other late for work because MTV was premiering the video of the Backstreet Boys’ “Backstreet’s Back.” We laughed at ourselves, at the video, and presented to each other our cultural and aesthetic analyses.

Before he moved out, I stole from our refrigerator door a photo of him chasing ducks in, I think, England. He was so expressive, every photo of him is rather extraordinary. But I love this one the most.

After I moved in with my boyfriend and he moved to Suffolk Street, he slept on the mattress I bought when I first moved to New York. When I broke up with the boyfriend, I got it back; he helped me drag it around the corner to Norfolk Street, where I’d gotten a sublet. After we hauled it up three flights, he said, “I’m not helping you move again.” He’d helped me three times by that point. I’m still sleeping on that mattress, which I realize is weird.

5.

For a few years in the early 2000s, Michael and I had a regular Tuesday late lunch at Pastis, a now-gone French bistro in the Meatpacking District. We’d invariably show up carrying our folded New Yorkers and discuss the issues of the day, from how Ashley Judd suddenly became a movie star to Franz Ferdinand’s debut album, from the absurd war in Iraq to the end of the American experiment (or things like that). And we also met regularly at the Phoenix, the gay bar in the East Village with the great jukebox and the massing of hipster gays before we had and then derided hipsters. We’d meet usually after whatever show he was working on, maybe midnight, and drink Bass and joke and talk about men, dating, sex, and Ashley Judd, Franz Ferdinand, the war, and the ends of America. I set him up a few times, and he dated a couple guys I knew, but nothing ever lasted, for reasons that always seemed perfectly logical (age, things in common, distance) but as a pattern seemed a bit more neurotic: maybe a fear of intimacy or an inability to be vulnerable. In our late 20s and early 30s, this didn’t seem too odd; he didn’t come out until he was 22, and he was a workaholic, travelled constantly, and that’s a hard way to find and keep a boyfriend. In our late 30s, this seemed sadder, and he never talked about that, beyond muttering to me late one night in his apartment in 2014 that dating is awful, that he had deleted all of the apps.

6.

His seeming lack of romantic experience didn’t mean he didn’t have valuable advice for me, or tough love. He told me bluntly when I was talking about some seemingly petty thing an ex had done to me, “You both did things that made everything worse.” He was right, and I now realize I did more of those things than my ex did. I was a lot less mature than I thought I was, and Michael was a lot wiser than his Muppet-ish affect indicated. When he and Steve started The Civilians and were asking for stories of lost objects for Gone Missing, I wrote to them, partly joking, that I’d lost several objects during the breakup with the aforementioned ex. I complained about it bitterly more often than I should have. Steve and Michael didn’t really respond to me, which made sense, as I was joking, mostly. Then, when I saw the show, the sixth song was “I Gave It Away.”

Been thinking about the way you left

and about the things you used to say

You said you had given me your heart

Said we would never be apartNow you call and ask to come on by

Say that you left things behind

and I could give you all your things

but why should I when you made me cry

Would you give my heart back to me?So if you’re missing the clothes you left by the bed

I gave them away

And those old books that you read

I gave them away

You chose to play with my headAnd if you lost all your power to sleep at night

If you lost your belief that things will be alright

You can’t find your strength or your will to fight

Well, I’ve got all that too and I’m not going to give it back.So if you’re missing the sheets you bought when we met

I gave them away

The dog you left at the vet

I gave her away

You lied, so that’s what you getAnd if you lost all your power to sleep at night

If you’ve lost your belief that things will be alright

You can’t find your strength or your will to fight

Well, I’ve got all that too and I’m not gonna give it, not gonna give it back.

It was the first time I saw the situation through someone else’s eyes, specifically that man’s. A lot of things made me grow up and realize my errors, but that song did as much, Michael did as much, as anything to engage my then under-developed humility.

Michael’s insight was unnerving, because it was so exacting but also because there was just so much of it. He could arrive in a room, a party, a bar, and he would light it up like a flash grenade. He could also suck the air out of it; sometimes it was impossible to get a word in edgewise, not because he needed to hear himself talk but because he had so much to say. But he was always listening, too, and watching. He understood people, he picked up on their motives and their desires, angers and sadnesses. You can see this most obviously in his lyrics, but if you had those late night beers with him, you’d get it in in his big, knowing eyes and those blunt statements like “You both did things that made everything worse.” That same trip in 2014, he watched me have an insane fight with my then boyfriend over the phone, and he didn’t need to tell me what he was thinking; his eyes said he was scared for me, sad for me. I saw all that, saw what I couldn’t see about myself and the pit I had fallen into.

7.

I spent my nine years in New York in journalism and publishing, and it was not what I had imagined it would be. I loved a lot of it, hated more, and even though I was doing well at work in 2005, I left New York to get a PhD in anthropology. One thing led to another, I had ended up writing my dissertation on HIV positive meth-using gay men and the public health industry surrounding them. When I saw Michael in 2014, I was in a postdoc at UCLA in HIV prevention. My adviser was one of the first psychologists to go to the Castro in 1981 to do research on what was to be called AIDS, and my office was in what had been UCLA’s original Center for AIDS Research and Education. I teach public health now, including the giant survey class at UC Irvine on AIDS.

I heard on Monday that a week before he was hospitalized for AIDS the first time, Michael told a mutual friend that I was one of the two people he’d ever known who had completely reinvented themselves. Michael was impressed by me, I was told. I can’t imagine that anyone as impressive as Michael could be impressed by me, but there was clearly a reason that he was my friend, even still. We had remained in close contact for many years, and then we spoke and saw each other less often, though when we did it was like it always was before. But it’s hard to hear that he was talking about how impressed he was by my transformation into an AIDS researcher and he was already sick, that he must have known something was very wrong.

8.

I came out in 1992, at the height of the epidemic in the United States and I have not and cannot think about my sexuality without simultaneously thinking about HIV and AIDS. I don’t know how to have sex without fear; even though that fear has lessened dramatically because of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and because of the success of treatment — the usual success, anyway — that fear is always, already there. Gay men are subcategorized by HIV status and prevention methods, not just when considering sexual partners but also when considering what it means to be citizen, how we are cared for or not by the government, how we are treated by strangers and family members and friends, what we keep secret, what we tell the world, what is means to be brave or in denial, to be risky or at risk or reckless. The gay art that Michael and I grew up on, the stuff that surrounded us in our teens and 20s is either explicitly or implicitly about AIDS, whether it’s Lips Together, Teeth Apart, Angels in America, or Falsettos, whether it’s The Line of Beauty, The Farewell Symphony, or Mysterious Skin, whether it’s Priscilla Queen of the Desert, Jeffrey, or Longtime Companion. Michael worked alongside ACT-UP veterans and veterans of the AIDS holocaust that struck New York’s theater community in the 1980s and 1990s. That boyfriend I treated poorly was both of those things; my subsequent relationships were as often serodiscordant as they weren’t. These are things Michael and I talked about a lot. We talked about how we were surrounded by individual and community, culture-wide cases of PTSD.

But we were also lucky. We came out into a world that was developing hope. We were both young enough that our contemporaries weren’t dying in droves. Until Michael died, I had not had a close friend die of AIDS, though I have dozens of friends with HIV. When I was finishing college, I wanted to go to grad school for medical anthropology and focus on AIDS and nationalism (or something like that), but I knew I wasn’t psychologically prepared for the sadness I would have had to deal with. By the time I got to my PhD, there was so much hope and most of the social science research was focused on how to get more people on the drugs, not on how death was everywhere, all of the time. That hope has made my work possible. And the point of my class at UCI is that we have the tools to end the epidemic. We just need to use those tools correctly and export those tools around the world, to get them into every community, rich and poor, black, white, and brown. The tools have been available for white, middle class, gay New Yorkers for 20 years. Men with Michael’s demographic profile are the least likely in the world to die from anything associated with HIV.

9.

How the fuck does Michael Friedman die of AIDS. How on earth was he only diagnosed as HIV positive in July, when he was also diagnosed with AIDS, because his T-cells were barely registering and he had several of the key opportunistic infections that automatically trigger that diagnosis. How did he have KS on his face for months before he went to the ER. How did no one notice that something was terribly wrong and drag him to the doctor. How did he not get tested for two years – or three years, depending on the story he had told people. How did the doctors, with all we know and all we can do, not save him. How the fuck did this happen. How did I not know.

I dropped all of the question marks from those sentences because they’re all rhetorical now; they don’t have answers, and I am only now asking the air, the sky, the Internet. Last week’s Times article – the paper’s third in a month on Michael – was basically all about how his friends, close and casual, as well as total strangers, are asking how this could happen, how the loss is devastating but the lack of answers and the seeming illogic of it all has compounded it.[3. The article didn’t make any attempt to answer the whys and hows, which was a huge disservice to its readers. Any HIV prevention professional could have provided a rundown of the various reasons someone doesn’t get tested or treated and dies so quickly after an AIDS diagnosis.]

When he confirmed to Liz and Jason what was making him sick, they asked if they should call and tell me. He told them he would call me. He never did. He had been in the hospital for a few weeks after the diagnosis and then at home, and then he got sick again and went back to the hospital. He was busy being very sick. The last week he was on a ventilator. Everyone thought he was going to pull through and then some infection got him that Saturday. Everyone thought I must have known.

Of course, I thought that if I’d been in New York, I’d have noticed something was wrong or I would have gotten him on PrEP before something had gone wrong or I would’ve reminded him to get tested. But he was surrounded by people like me. It sounds like he brushed off the concerns, ignored the slowly broiling situation in his body, until it wasn’t possible anymore.

It’s not my fault, and I know I couldn’t have done anything. But. But I’ve spent the last ten years of my life as an AIDS researchers and educator, and one of my best friends died of AIDS. He didn’t call me, and it feels a deliberate, maybe because of what he feared I might ask or say. It’s not my fault, but it’s not not my fault either. I’m inept. I’m powerless. It’s not my fault. It is.

I don’t get it. I cannot fathom how it could happen: How he could have died of something that was easily prevented and easily treated and how he could be gone.

And yet I can fathom it. I’ve lectured about how the stigma of AIDS makes the HIV test terrifying,[4. All one needs to do is read the comments on any of the articles about Michael’s death to see how the stigma of HIV and AIDS travels through our culture. Even if you fully and completely own your diagnosis, you face so much stress, anger, pity, fear, revulsion, and confusion. It makes sense that people are afraid.] how the cognitive dissonance of an HIV diagnosis (from a doctor or from your own conclusions) can be resolved in unhealthy ways like denial, and I’ve written about how anxiety and depression increase the risk of infection and make treatment more difficult, if it’s even started. I can fathom how Michael could not get tested for years, how he could ignore that his body was ringing the alarms, how he could dissemble when asked about all of this by his terrified and maybe angry friends and family. He could be depressive and secretive, compartmentalized and, honestly, weird. I can fathom it happening.

10.

It never crossed my mind that Michael could ever not be there. I assumed he’d always be in New York or Williamstown or Hong Kong or London or anywhere, somewhere collaborating on a new musical or visiting an old friend for a wedding or a needed rest on the beach. Maybe he’d pop up in LA and we’d get martinis. As I was flying to New York for his memorial, I involuntarily imagined having dinner with him, assumed I’d be staying at his apartment in Fort Greene. We hadn’t actually spoken in 18 months, though we’d exchanged texts, the last one on April 1. While at Burning Man, I was thinking that I needed to make time to see him. I had been overwhelmed by my first year at UCI, and before that I’d been depressed and isolated and hadn’t reached out to anyone. He hadn’t made time for me, either, but I knew he was busy, that the current political and cultural and social situation was despairing, as it is for me and the rest of our friends. But something else was going on, and we’ll never know what it is. There won’t be a Rosebud at the end of this or anyone else’s essay.

It never crossed my mind that Michael could ever not be there. I assumed he’d always be in New York or Williamstown or Hong Kong or London or anywhere, somewhere collaborating on a new musical or visiting an old friend for a wedding or a needed rest on the beach. Maybe he’d pop up in LA and we’d get martinis. As I was flying to New York for his memorial, I involuntarily imagined having dinner with him, assumed I’d be staying at his apartment in Fort Greene. We hadn’t actually spoken in 18 months, though we’d exchanged texts, the last one on April 1. While at Burning Man, I was thinking that I needed to make time to see him. I had been overwhelmed by my first year at UCI, and before that I’d been depressed and isolated and hadn’t reached out to anyone. He hadn’t made time for me, either, but I knew he was busy, that the current political and cultural and social situation was despairing, as it is for me and the rest of our friends. But something else was going on, and we’ll never know what it is. There won’t be a Rosebud at the end of this or anyone else’s essay.

Several people told me that the memorial might bring me closure — if that’s possible, as closure and catharsis are somewhat mythical things. But rituals – weddings, funerals, bar mitzvahs — can create cognitive bridges, transitions from one period of life to the next, the period with Michael and the future without. The memorial was extraordinary, beautiful and funny and exhausting and so, so sad. While waiting for the memorial these several weeks, I was scared of how I’d feel, but also scared that the bridge would be crossed. It has. I’m finally able to finish this essay I started writing three days after Michael died.

11.

When I started writing this, I couldn’t remember when I’d last seen him. I had reread emails and texts and piece it all together. Finally, I realized it was almost exactly two years ago. I had lunch with Michael at a diner near Penn Station on a rainy afternoon in October of 2015. I was on my way to Curtis’s wedding in Duchess County. I’d taken the train from the Newark airport, and before I took the Metro North to Poughkeepsie, I met Michael. I barely remember anything. I think he was wearing a white button down short, barely tucked in, and fraying a bit on the collar and cuffs, and well-worn khakis. He was in sneakers I think. He had an umbrella. He was happy to see me, I think. I assume. I probably got a tuna melt. I don’t know what we talked about. It was supposed to be just another lunch, like the hundreds before and the many to come, so I didn’t need to commit it all to memory. It wasn’t supposed to be the last time, because he should be still be here.